¿Da el clima "pasos de borracho"?

Una de las pegas de la “ciencia del cambio climático”, bastante clara a estas alturas, es la burricie en ciencia estadística del ramo. Los estadísticos señalan que el clima, comparado con otras ciencias, está en una situación muy especial. Es un sistema terriblemente complejo sobre el que no se pueden hacer experimentos. En las ciencias en las que se pueden comprobar las hipótesis en el laboratorio, el análisis de los resultados se puede hacer con una estadística relativamente rudimentaria. Pero el caso del clima se parece más al de los análisis económicos, que precisa unas herramientas estadísticas de muy alto nivel.

Es muy frecuente la protesta de los estadísticos profesionales y académicos sobre lo que están haciendo los chicos del cambio climático. Ya ha varios trabajos de gente de econometría protestando por los análisis del IPCC y adjacentes. Y no en vano son los que mejores herramientas conocen y manejan a la hora de estudiar series temporales de datos (por ejemplo las temperaturas, o por ejemplo el índice de una bolsa de valores).

El último trabajo en esa línea lo ha resaltado Roger Pielke (padre):

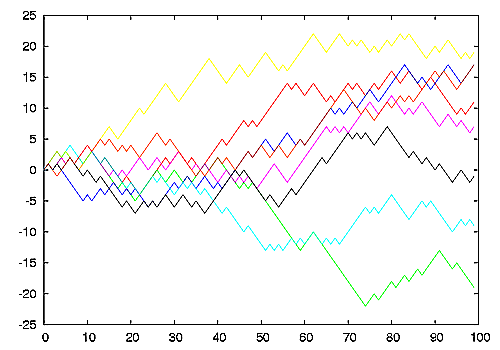

El estudio muestra que del registro de temperaturas que tenemos (1850 - 2010) lo que se deprende es la presencia de un "camino_aleatorio" (RW o Random Walk en inglés), que se ve bien en períodos de unos 30 años.Una forma de explicar el concepto es compararlo con el caminar de un borracho. La posición del borracho en cada momento depende la posición anterior, más un pequeño movimiento aleatorio. Así que va dando vueltas por ahí sin ninguna dirección determinada. Y no sabes si los próximos cinco minutos le van a llevar hacia la derecha o hacia la izquierda. En dibujo de Wikipedia:

Por supuesto que si el registro de temperaturas es un "camino aleatorio", o tiene un componente de camino aleatorio, la manera de analizar la tendencia, y de interpretar lo que está pasando, cambia por completo. Sin embargo, la gente del IPCC no quiere contemplar nada de esta aparentemente muy posible circunstancia. No tienen los conocimientos para hacerlo, ni tampoco las ganas de pedir ayuda a los que tienen los conocimientos. Al contrario, lo que hicieron en el último informe del IPCC (AR4 - 2007), es borrar las escasas menciones que había sobre el problema.

Por supuesto que si el registro de temperaturas es un "camino aleatorio", o tiene un componente de camino aleatorio, la manera de analizar la tendencia, y de interpretar lo que está pasando, cambia por completo. Sin embargo, la gente del IPCC no quiere contemplar nada de esta aparentemente muy posible circunstancia. No tienen los conocimientos para hacerlo, ni tampoco las ganas de pedir ayuda a los que tienen los conocimientos. Al contrario, lo que hicieron en el último informe del IPCC (AR4 - 2007), es borrar las escasas menciones que había sobre el problema.

Hay unos cuantos ejemplos de estadísticos señalando esta circunstancia sobre las temperaturas y su interpretación. Por ejemplo, otro es:

- Is Global Warming Real? Analysis of Structural Time Series Models of Global and Hemispheric Temperatures.

Ross McItrick, economista que participa en la discusión del clima con interesantes publicaciones en la literatura científica, explica y resume este desencuentro entre los gamberros del cambio climático y la ciencia estadística. En la discusión en WUWT [-->]:

Terence Mills also has a very important paper on representation of trends in climate data series in a recent volume of Climatic Change.Since the late 1980s there has been a steady stream of papers by econometricians and time series analysts looking at whether temperature is a random walk. It is possible to find conclusions on both sides, as well as the intermediate cases of fractional integration, though my impression is that the longer the data sets get, the more likely it is to find RW behaviour. Mills’ conclusion is that the current data sets are best represented by a combination of RW, trend and cyclical components, but a researcher still has some leeway to specify the trend model. Nonetheless, the model getting the most support in the data indicates RW behaviour and yields a contemporary trend component well below GCM forecasts.

This is an area where it is difficult to fully convey how important the underlying question is. The qualitative difference between a data series that contains a random walk and one that doesn’t is enormous. It is completely routine in economics to test for RW behaviour, or as it is known more formally, unit root processes. If your data contain a unit root it simply comes from another planet than non-unit root data, and you have to use completely different analytical methods both to estimate trends and to fit explanatory models. Conventional methods are built on the assumption of stationary processes that converge to Gaussian distributions in the limit. But unit roots are non-stationary and they do not converge to Gaussian limits. They also imply some fundamental differences about the underlying phenomena, namely that means, variances and covariances vary over time, so any talk about (for example) detecting climate change is very problematic if the underlying system is nonstationary. If the mean is variable over time, observing a change in the mean is no longer evidence that the system itself has changed.

If the IPCC knew enough about this issue to deal with it properly they would have an entire chapter, if not an entire special report, devoted to the question of whether climate is nonstationary and over what time scales. Until this is known there is a very high probability that a lot of statistical analysis of climate is illusory. If that seems harsh, ask any macroeconomist about the value that can be placed on empirical work in macro prior to the 1987 work of Engle and Granger on spurious regression. They wiped out more than a generation’s worth of empirical work, and got a Nobel Prize for their efforts.

If the IPCC were willing or able to deal with this issue, there are a lot of qualified people who could contribute–people of considerable expertise and goodwill. Unfortunately the only mention of the stationarity issue in the AR4 was a brief, indirect comment inserted in the second draft in response to review comments:

Determining the statistical significance of a trend line in geophysical data is difficult, and many oversimplified techniques will tend to overstate the significance. Zheng and Basher (1999), Cohn and Lins (2005) and others have used time series methods to show that failure to properly treat the pervasive forms of long-term persistence and autocorrelation in trend residuals can make erroneous detection of trends a typical outcome in climatic data analysis.There was also a comment in the chapter appendix cautioning that their “linear trend statistical significances are likely to be overestimated”.

Sometime after the close of IPCC peer review in summer 2006 the above paragraph was deleted, the cautionary statement in the Appendix was muted, and new text was added that claimed IPCC trend estimation methods “accommodated” the persistence of the error term. We know on other grounds that their method was flawed–they applied a DW test to residuals after correcting for AR1, which is an elementary error. The email traffic pertaining to the AR4 Ch 3 review process (not in the Climategate archive, but public nonetheless, if you know where to look) shows that the Ch 3 lead authors knew they were in over their heads. But rather than get help from actual experts, they just made up their own methods, and then after the review process was over they scrubbed the text to remove the caveats inserted during the review process. [–>]